By Clínica Maslow

Many runners and active patients come to the clinic complaining of persistent pain on the lateral side of the knee, especially during running, squats, or stair climbing. In most cases, the source is the iliotibial band (ITB), a structure under constant tension that, when poorly managed, leads to friction and recurring discomfort.

But the real problem isn’t just the pain… it’s what you can’t see: muscle imbalances that alter movement. What if the TFL is overworking? What if the gluteus medius isn’t activating properly?

Without objective tools, these dysfunctions can go unnoticed, become chronic, and complicate treatment. With surface electromyography (EMG), you can see exactly which muscles are active, which are compensating, and which are inhibited, even when biomechanics seem fine.

Want to learn how to identify these patterns in your patients and use data to decide what to work on?

Schedule a free call with an EMG-trained physiotherapist. Just 10 minutes. 100% personalized.

In this post, you’ll learn through a real clinical case where EMG analysis was key to understanding the cause of pain, planning treatment, and accelerating the patient’s recovery.

What Is the Iliotibial Band and Why Can It Hurt?

The iliotibial band is a strip of connective tissue running along the outside of the thigh, from the pelvis to the tibia. Its main function is to stabilize the leg during movements involving knee flexion and extension, like running, squatting, or descending stairs.

But when the muscles associated with it don’t work in coordination, the ITB starts to rub against the lateral femoral condyle, causing inflammation, overload, and pain.

What Is a Muscle Imbalance and How Does It Relate to the ITB?

A muscle imbalance occurs when some muscles are overactive and others are underactive. In ITB syndrome, this can lead to excessive tension, hip instability, and repeated friction near the knee.

The most common imbalance patterns we see:

- – TFL (Tensor Fasciae Latae): Often overactive, placing continuous tension on the ITB

- – Vastus Lateralis: May be hyperactive, pulling on the patella and increasing lateral knee stress

- – Gluteus Medius: Frequently underactive, failing to properly stabilize the pelvis

This triangle of imbalance creates the ideal conditions for ITB-related symptoms to appear.

What Symptoms Does Your Patient Present?

Early symptoms of ITB syndrome may be subtle, but often progress to a recognizable pattern:

- – Sharp or burning pain on the outer side of the knee, especially during running or stair use

- – Tightness along the outer thigh, unrelieved by stretching

- – A sense of instability during lunges, deep squats, or direction changes

Without proper intervention, this pain can become chronic and significantly limit performance.

EMG Assessment: Martín’s Real Case

Martín, a 32-year-old recreational runner, came to the clinic with a recurring issue: constant pain on the outside of his left knee when running more than 20 minutes or doing deep squats.

He had tried stretching, foam rolling, changing shoes, nothing really worked.So, we decided to assess his muscle activation patterns using surface EMG. We wanted objective insights into what was happening with the muscles connected to the ITB.

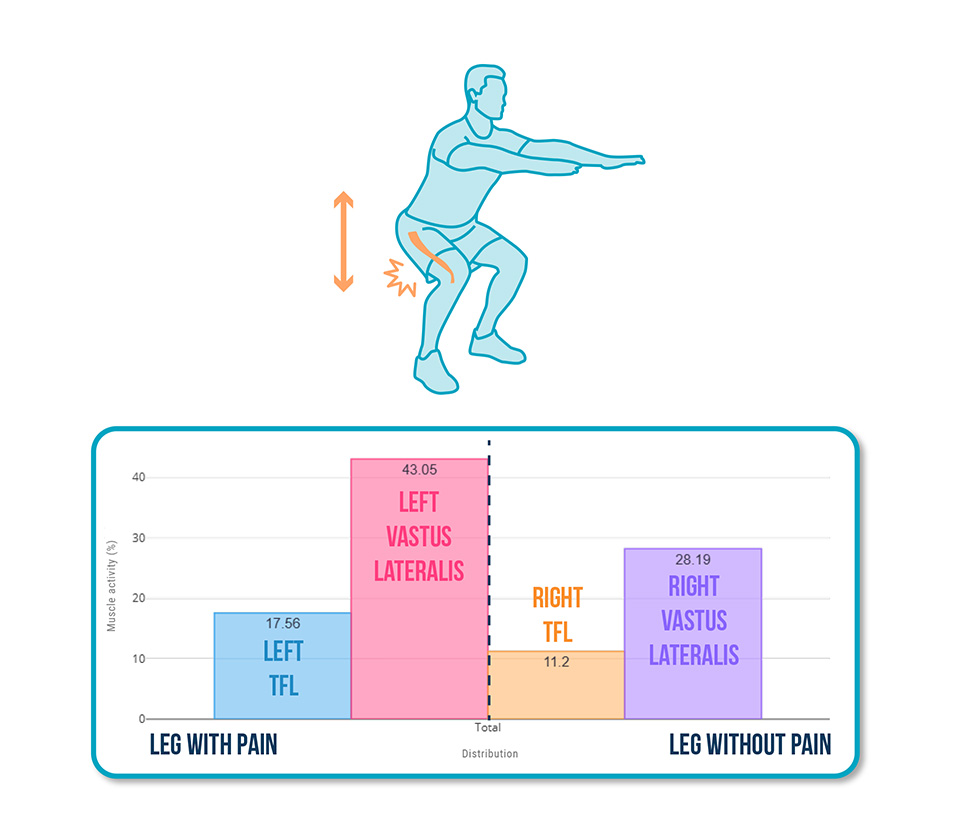

Step 1: Squat Assessment

We asked Martín to perform several squats. Electrodes were placed on the gluteus medius, TFL, and vastus lateralis. The EMG data was clear:

- – Overactive left TFL (❌)

- – Excessive activation in the left vastus lateralis (❌)

The ITB was being overloaded by a poorly adapted compensation pattern—and visually, everything looked fine. Movement control appeared normal.

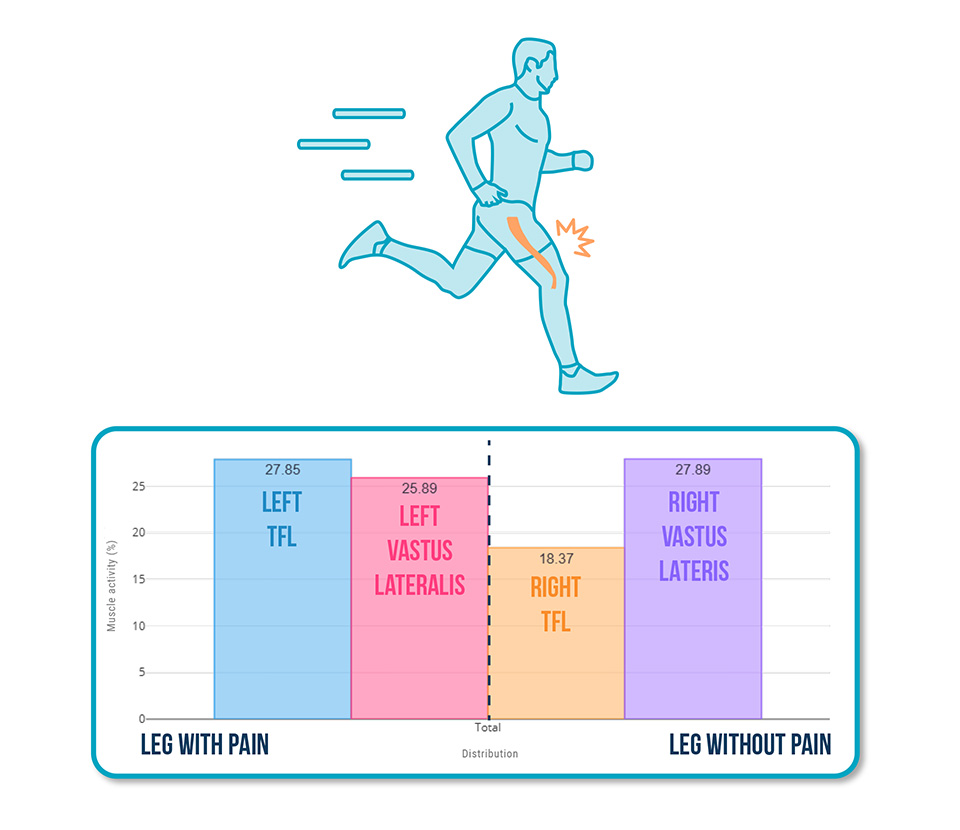

Step 2: Running Assessment

The next test was even more revealing. We placed the sensors and analyzed Martín’s running pattern on a treadmill. The results?

✅ Gluteus medius function was adequate, but:

❌ Left TFL was hyperactive → Overloading the ITB and increasing friction at the knee

Why Use EMG in These Cases?

Without EMG, this pattern would have gone unnoticed. The analysis allowed us to:

- – Detect invisible compensations

- – Objectively measure which muscles were underperforming during real exercises

- – Design a treatment strategy based on the patient’s actual data

We also used EMG biofeedback, allowing Martín to learn how to correctly activate his glutes and reduce overactivity in the TFL and vastus lateralis in real time.

Conclusion

EMG has proven to be a key tool to:

- – Identify the neuromuscular origin of ITB pain

- – Personalize treatment based on which muscles need to be activated—or deactivated

- – Boost patient confidence by helping them see and understand their own activation patterns

Want to learn how to apply EMG in your clinical assessments?

See you in the next post! 🙂